CONDITIONS

AMD (Age-related Macular Degeneration)

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a deterioration or breakdown of the eye’s macula. The macula is a small area in the middle of the retina. The macula is the part of the retina that is responsible for your central vision, allowing you to see fine details clearly.

There are two types of macular degeneration: the dry and wet forms.

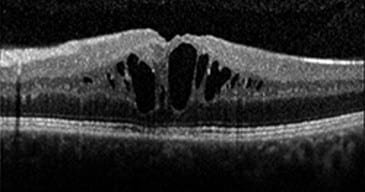

Dry AMD

The dry form is a slow deterioration of the macula causing blurry or distorted vision. The majority of the population who suffer from AMD have the dry form. Dry AMD is a slow deteriorating condition, and there is no treatment for it at this time.

If you have the dry form, it is very important to monitor your eyesight. If you ever notice any changes, call your ophthalmologist right away. We strongly recommend taking eye vitamins such as I-Caps, Ocuvite, or PreserVision. These vitamins contain the nutrients your retina needs to help slow down the disease.

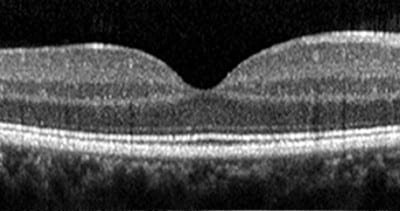

Wet AMD

The wet form is the more aggressive of the two. It is caused by the formation of new blood vessels (neovascularization) under the retina that leak fluid, causing distortion, blurriness, or even black spots in the center of your vision. While this form can be aggressive, there is treatment available.

The most effective treatment is to inject medicine into the back of your eye. Medicines such as Avastin, Lucentis, and Eylea are designed to slow the progression of the disease. Molecules in the medicines “latch” onto growth hormones and help prevent bleeding.

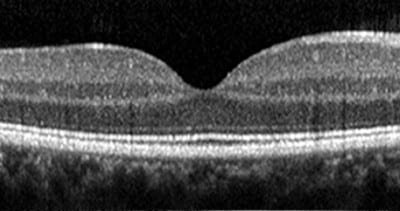

Below are examples of three OCTs (scans of the retina): normal, wet AMD, and dry AMD:

Normal Retina

Wet AMD

Dry AMD

Retinal Occlusions

A stroke affecting the eye, also known as a retinal occlusion, is a blockage of the blood vessels in your retina. The blockage is caused by a clot or occlusion (narrowing or closure) in a blood vessel or a buildup of cholesterol in a blood vessel. This causes the walls of the vein to leak blood and excess fluid into the retina. Fluid collects in the macula (the area of the retina responsible for central vision), and vision becomes blurry.

There are several types of strokes involving the eye that affect either the veins in your eye or the arteries. Veins are the blood vessels that carry blood toward your heart. Arteries are the blood vessels that carry blood away from your heart.

Branch Retinal Vein Occlusion (BRVO)

This is a blockage of the small veins of your retina.

Branch Retinal Artery Occlusion (BRAO)

This is a blockage of the small arteries of your retina.

Central Retinal Vein Occlusion (CRVO)

This is a blockage of the main vein of your retina.

Here is a video of a fluorescein angiogram documenting a central retinal artery occlusion.

Central Retinal Artery Occlusion (CRAO)

This is a blockage of the main artery of your retina.

Here is a video of a fluorescein angiogram documenting a central retinal artery occlusion.

Choroidal Melanoma

Choroidal melanoma (also called uveal melanoma) is a cancer of the eye involving the iris, ciliary body, or choroid (collectively referred to as the uvea). Tumors arise from the pigment cells (melanocytes) that reside within the uvea and give color to the eye. These melanocytes are distinct from the retinal pigment epithelium cells underlying the retina that do not form melanomas.

Often, the malignant tumors grow from a nevus (similar to a freckle). Just as a freckle is flat on your skin, the nevus should be flat in the eye. If the nevus starts to grow over time or becomes thick, it may be malignant.

If you are diagnosed with choroidal melanoma, you should have frequent check-ups to make sure the melanoma does not spread throughout your body. Treatment for melanoma usually consists of radiation therapy, and in some cases, the eye will be enucleated (removed).

Choroidal Nevus

A nevus in the eye is a common, benign, pigmented growth similar to a mole or freckle on your skin. A nevus can occur either in the front of your eye, around the iris (colored part of the eye), or beneath the retina in the back of the eye. A nevus beneath the retina is called a choroidal nevus. Sometimes it is called a “freckle in the eye.”

If you are diagnosed with a nevus, you should have regular check-ups to make sure there is no change in its color, shape, or size. Just like a mole on your skin, a nevus in your eye can potentially turn into melanoma.

Cystoid Macular Edema

Cystoid macular edema occurs when fluid and protein deposits collect in the macula (the center of the retina) and cause it to thicken and swell (edema). The swelling may distort a person’s central vision, as the macula is the center of the retina at the back of the eye. This area holds tightly packed cones that provide sharp, clear central vision to enable a person to see detail, form, and color that is directly in the direction of gaze.

Ocular surgeries have been known to cause temporary cystoid macular edema. Conditions such as Uveitis and Vein occlusions can cause swelling in the macula as well.

Normal Retina

Cystoid Macular Edema

Central Serous Retinopathy

In central serous retinopathy (sometimes called central serous choroidopathy), fluid builds up under the retina and distorts vision. Fluid leakage is believed to come from a tissue layer with blood vessels under the retina called the choroid. Another layer of cells called the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) is responsible for preventing fluid from leaking from the choroid under the retina. When, for unknown reasons, tiny areas of the RPE become defective, fluid builds up and accumulates under the RPE, much as the liquid in a blister collects under the skin. As a result, a small detachment forms under the retina, causing vision to become distorted.

Central serous retinopathy (CSR) is generally found in men in their 40s. Stress has been found to be a contributing factor for this condition. The recommended “treatment” is stress management. Below is an example of a patient who had CSR. After he was informed that this is brought on by stress, he managed his stress much better, and the pocket of fluid was gone the following month. There are other treatment options available if the fluid does not resolve after several months, such as oral medication or intravitreal injections.

Diabetic Retinopathy

There are two types of diabetic retinopathy.

Non-Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy (NPDR)

This type is the earliest stage of diabetic retinopathy. With this condition, damaged blood vessels in the retina begin to leak extra fluid and small amounts of blood into the eye. Sometimes, deposits of cholesterol or other fats from the blood may leak into the retina.

Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy (PDR)

This type mainly occurs when many of the blood vessels in the retina close, preventing sufficient blood flow. In an attempt to supply blood to the area where the original vessels closed, the retina responds by growing new blood vessels. This is called neovascularization. However, these new blood vessels are abnormal and do not supply the retina with proper blood flow. The new vessels are also often accompanied by scar tissue that may cause the retina to wrinkle or detach.

Endophthalmitis

Endophthalmitis is an inflammation of the internal coats of the eye. It is a possible complication of all intraocular surgeries, particularly cataract surgery, possibly resulting in loss of vision and the eye itself. Infectious etiology is the most common, and various bacteria and fungi have been isolated as the cause of endophthalmitis. Other causes include penetrating trauma and retained intraocular foreign bodies.

In cases of endophthalmitis, one usually finds a history of recent intraocular surgery or penetrating ocular trauma. In some cases of metastatic endophthalmitis—particularly in immunocompromised patients or those with diabetes—the spread of infection may have been hematogenous (via the bloodstream).

Endophthalmitis is usually accompanied by severe pain, loss of vision, and redness of the conjunctiva and the underlying episclera. Inflammation of the various coats of the eye is also present. Hypopyon can be present in endophthalmitis and should be looked for on examination by a slit lamp.

If you have endophthalmitis, you need an urgent examination by an ophthalmologist and/or vitreo-retina specialist. A specialist will usually decide on urgent intervention, providing an intravitreal injection of potent antibiotics and preparing for an urgent pars plana vitrectomy as needed. In severe cases, enucleation may be required to remove a blind and painful eye.

Epiretinal Membrane/Macular Pucker

An epiretinal membrane (macular pucker) is a layer of scar tissue that grows on the surface of the retina, particularly the macula (the part of your eye responsible for detailed, central vision). As we grow older, the thick vitreous gel in the middle of our eyes begins to shrink and pull away from the macula. As the vitreous pulls away, scar tissue may develop on the macula. Sometimes the scar tissue can warp and contract, causing the retina to wrinkle or become swollen or distorted.

The only treatment option is surgical removal of the scar tissue from the macula. After having the surgery, your vision will be poor because a gas bubble was placed into the back of the eye since the gel that occupies that back of the eye was removed. Over the course of several weeks, the bubble will get smaller and eventually go away as your eye produces fluid to occupy the space.

Before Surgery

After Surgery

Ocular Histoplasmosis

Ocular histoplasmosis or presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome (POHS) is an ocular manifestation of a fungal bacteria found in birds. Histoplasmosis, when active, can cause bleeding in the retina (choroidal neovascularization) where “punched out” lesions are present.

Treatment at this time is only for the bleeding in the retina. Anti-VEGF (anti-vascular endothelial growth factor) is injected into the eye to help prevent active bleeding. If the histoplasmosis lesions appear to be “inactive” or not bleeding, then you will just need regular dilated exams for monitoring.

Macular Hole

The macula is a very small area at the center of the retina. Light rays are focused onto the retina where they are transmitted to the brain and interpreted as the images you see. The macula is responsible for your pinpoint vision, allowing you to read, sew, or recognize a face.

As we grow older, the thick vitreous gel in the middle of our eyes shrinks and pulls away from the macula. If the gel sticks to the macula and doesn’t pull away, the macular tissue stretches and eventually tears, forming a hole.

Before Surgery

After Surgery

Retinal Detachment

The retina is a thin transparent layer at the back of the eye. When light enters the eye, it is displayed onto the retina. Once the light stimulates the retina, it creates electrical impulses that travel through the visual pathway and to the back of the brain (the occipital lobe). The choroid is behind the retina, and it supplies the retina with the blood and nutrients it needs to function.

There are many different things that can contribute to a retinal detachment. People who are very nearsighted tend to have an elongated eye, and that makes them more susceptible to a retinal detachment. Sometimes blunt trauma can cause a retinal detachment. Large amounts of bleeding from diabetic retinopathy or exudative (wet) age-related macular degeneration can cause the retina to be pulled off by all the blood underneath it.

Age is also a contributing factor. As we get older, the vitreous (the clear gel that occupies the space in the back of the eye) starts to liquefy and shrink. As the vitreous shrinks, it separates from the retina and can tear it. If fluid gets under the tear, it can cause the retina to detach.

There are three types of retinal detachments: rhegmatogenous, tractional, and exudative.

Rhegmatogenous

A rhegmatogenous retinal detachment occurs due to a break in the retina (called a retinal tear) that allows fluid to pass from the vitreous space into the subretinal space.

Tractional

A tractional retinal detachment occurs when fibrous or fibrovascular tissue that is created by an injury, inflammation, or neovascularization pulls the sensory retina away from the retinal pigment epithelium.

Exudative

An exudative retinal detachment occurs due to inflammation, injury, or vascular abnormalities that result in fluid accumulating underneath the retina without the presence of a hole, tear, or break.

In an evaluation of retinal detachment, it is critical to exclude exudative detachment, as surgery will make the situation worse, not better. Although rare, exudative detachment can be caused by the growth of a tumor on the layers of tissue beneath the retina (the choroid). This cancer is called a choroidal melanoma.

Retinoschisis

Retinoschisis is an eye disease characterized by the abnormal splitting of the retina’s neurosensory layers, usually in the outer plexiform layer. Most common forms of this disease are asymptomatic; some rarer forms result in a loss of vision in the corresponding visual field. Retinoschisis is often misdiagnosed as a retinal detachment due to the similarity of the two.

Retinal Tear

A retinal tear happens when the vitreous gel that occupies the space in the back of your eye pulls on the retina and creates a tear. As we get older, the vitreous gel starts to shrink and will separate from the retina. Sometimes pieces of the gel break off and float around (that is called a floater). Occasionally, there will be a spot with more adherence, and when it pulls away from the retina, it will make a tear. When this happens, people notice flashes of light or more floaters.

If you notice this, you should see an ophthalmologist to determine if you have a tear. If fluid goes in where the tear is, it will cause a retinal detachment. To treat a retinal tear, the doctor will laser around the tear to secure the retina.

Uveitis/Chorioretinitis

Uveitis is the inflammation of the uvea, the middle layer of the eye. The uvea consists of the iris, choroid, and ciliary body. The choroid is between the retina and sclera (the white part of the eye), and it provides blood flow to the layers of the retina. The most common type of uveitis is an inflammation of the iris called iritis. Infections, injury, and autoimmune disorders may be associated with the development of uveitis.

Uveitis can be serious, leading to permanent vision loss and glaucoma. Early diagnosis and treatment are important to prevent the complications of uveitis.